Egoless Intelligence

Maya handles the crayon deftly, as if she’s been drawing for years. Her marks seem purposeful, even if a clear image doesn’t seem to be emerging. She occasionally makes quick scribbles, moving her tool brashly, and at other times softly and slowly, tapping into a creative energy I can only imagine. When she’s finished, she tosses her crayon away and walks away from her creation, a small intermission in her day. She doesn’t sit to ponder its meaning, to decide whether or not it needs more (or less); and just as promptly as she first took the crayon to make her marks did she walk away after she knew, with that kind of childlike certainty, that the piece was complete.

When you see her final image, you can’t help but be humbled. To comprehend what you’re seeing isn’t to try to rationalize the piece, but to simply see it as it is. Asking whether the drawing is any good feels as reductive as asking whether a flower looks any good. Like seeing a photo of the forest and claiming to have seen some trees rather than camping in the wilderness.

After a short break Maya and I discuss some matters of importance:

Me: Maya, will you draw me a bird?

Maya: No, I don’t want to.

Me: Why not? Will you draw me something else instead?

Maya: No, let’s play magna-tiles now!

Me: Oh! Should we make something fun? How about a birdhouse?

Maya: Yeah, that’s a good idea!

We sit and play for a while. My initial ideas to make a birdhouse are improved upon and we build more interesting structures: towers, pyramids, ice cream cones, and other nameless creations. One looks like a mix between a tetrahedron and a dog. Another serves as an adequate home for “baby squirrel”, until Maya decides to smash it flat with her foot. She giggles and then bursts out into full-bellied laughter, the cackle moving through her small body and shaking her to her core. She lets herself fall to the ground, clutching and trying to hold in how terribly funny it all is. The pristine, beautiful designs we had put so much thought and care into so easily blown to smithereens. Oh how viscerally Maya understands the fleeting nature of attachment and the impermanence of reality.

For a long time, Maya didn’t seem to be doing anything, but then all of a sudden, it’s like her mind woke up. She seemed to reach an inflection point around 6 months of age, when she realized she could not only be affected by the world, but make changes in it that she, herself, willed. The box could be pushed over, the food could be thrown on the ground, and a cry made our heads turn.The complexities of her interactions and second-order effects of her changes became more apparent as she grew; a scream properly done could elicit sympathy, but if done incessantly only incited frustration and exhaustion in her parents.

Soon, her will became apparent through a recursive definition of herself. When she looked in the mirror she knew the little girl in the reflection was really “her” and what she wanted and what the image of herself, “Maya”, wanted became inseparable. “Maya doesn’t like veggies” became “I don’t want veggies” and “Maya likes sardine sandwiches” is now “I like sardines, I do, I do!”.

Is Maya intelligent? Maya doesn’t think her way through the world more than she feels her way through it, and why should she? She’s not keeping a schedule. She doesn’t need to pack her own lunch, get herself to school on time, or board a flight. Her world and sense of time is entirely captured in the eternal present: moving, shifting, and reacting without hesitation with the panache of a zen master and the toilet control of a 3 year old.

This has less to do with her personality and more to do with her brain development. Her prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning, reasoning, and decision making, isn’t fully formed yet. Her formation of ego and self provides her a way to speak English more naturally (i.e. using the first rather than the third person) as opposed to acting as a virtualized stand-in for herself. As adults we use our egos as a means of planning, planning reactions, and then planning reactions to those reactions, but I doubt Maya is capable of that level of executive function just yet.

She is nothing if not creative though. It’s unclear how much of a “plan” Maya forms in her head before drawing or engaging in some creative act. In fact, if we examine our own, truly creative or connected experiences, we might find a lot of the same: creativity flows out of us rather than being forced out. Creativity is also not simply “randomness”, because randomness is defined with disconnection in mind. If we were to randomly color something, it would mean we do so without any regard for the structure or organizational principles the piece needs. If a child’s drawings seem random to us, maybe it’s because we’re not listening to what the child is actually saying.

Maya along with other children her age, demonstrate high amounts of sentience and creativity, even if they’re not particularly intelligent yet. We raise our young and prepare them for an uncertain and unforgiving world, one where they will need to use their intelligence to survive. But we don’t train them in the same way to be creative. We assume that their interiority and creativity will sustain and continue to grow as they age.

Intelligent Machines

In the last few years we’ve been given new tools that promise ways to tap into massive, creative potential hitherto unseen, and now we’re on the brink of producing AI that can not only write long-form prose, but code, provide companionship, therapize, and create images and videos at the tap of a finger. Maya may not draw me a bird, but ChatGPT most certainly will if I ask it to.

But even though we say things like: “ChatGPT wrote this essay” or “ChatGPT drew this image”, behind the scenes there is a different story. ChatGPT and any other LLM for that matter, are statistical machines, producing tokens or modifying pixels iteratively to maximize an objective function. The magic we see is the magic of mathematics: encoding the spaces of language, images, and sound into parallel domains in math. It just so happens that computing machines work very well in the mirror realm.

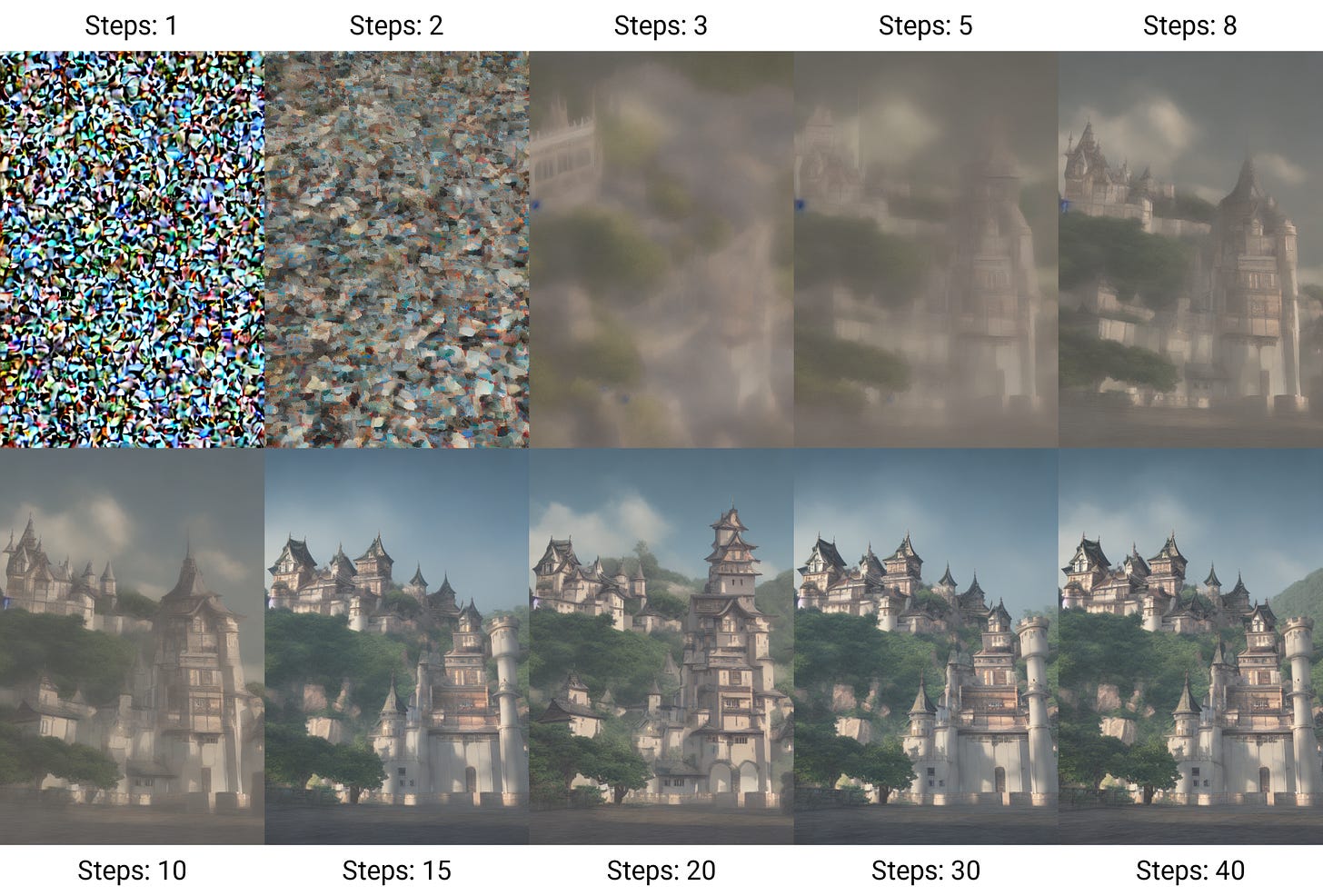

Generative AI doesn’t draw an image the way you or Maya might, forming marks and strokes that gradually come together into a cohesive image. Generative AI uses techniques like stable diffusion, slowly extracting an image from random noise and refining it iteratively until it’s done.

Although the artifact at step 40 looks like it was drawn, it wasn’t. Drawing is what humans do; this was produced by an AI in an entirely new way. This is not to say that the produced image isn’t good or that the process AI takes is wrong, it’s just not what humans would or ever could do; it is fundamentally different.

At the same time, many argue that we’re building machines that are growing faster and faster in general intelligence, not just in the ability to produce artifacts. The argument generally goes like this: AI’s can be objectively graded on a sort of “intelligence scale”. Humans are somewhere on this scale, and as we make smarter and more capable AI’s, at some point we’ll have one that more or less reaches human intelligence. At this point we have an AGI (artificial general intelligence). Once machines have achieved AGI, they’ll be able to recursively improve themselves, until reaching ASI (artificial super intelligence). Afterwards, we don’t really know what the values or motives of an ASI would be and so speculating after this is futile.

There is a popular thought experiment told by AI safety and ethics researchers about a runaway scenario in which a misaligned ASI is given a seemingly innocuous goal with disastrous goals. Philosopher Nick Bostrom imagined this in 2003, not as a prediction of what AI would necessarily do, but as a warning of what could come:

Suppose we have an AI whose only goal is to make as many paper clips as possible. The AI will realize quickly that it would be much better if there were no humans because humans might decide to switch it off. Because if humans do so, there would be fewer paper clips. Also, human bodies contain a lot of atoms that could be made into paper clips. The future that the AI would be trying to gear towards would be one in which there were a lot of paper clips but no humans.

Of course, the AI might pursue its goal very creatively. For example, a plan to exterminate all humans might include bioengineering deadly viruses and releasing them in hot spots to incite rioting, political violence, and self-destruction of the human race. After we’ve destroyed ourselves the AI can continue to work on its goal of producing more paper clips quietly until the end of time. But the interesting thing is that we don’t actually need an ASI to have runaway outcomes. In many ways, we’ve already begun to build organizational intelligences that behave in precisely this way: corporations1.

Corporations, especially tech startups and companies in Silicon Valley, are incentivized to grow insanely quickly, metastasizing into unsustainably large entities, hell-bent on increasing their market share and margins. These tactics are often executed in misaligned ways with our own human values and take advantage of existing financial systems to raise large amounts of cash and consumer hype, but if you dive into a corporation you’ll see there is no individual person who owns every decision end-to-end. The machine operates at a higher level than any individual person, and this is a feature, not a bug, of the organization.

In Unaccountability Machine, economist Dan Davies writes about precisely this problem and how corporations are specifically designed as “accountability sinks” to avoid singular blame for any individual. A CEO must answer to the shareholders, a team must report to their manager, and a high-level lead must “act in the best interests of the company”. If the goal of a company is to bring about AGI, many scorched-earth strategies become completely justified, because AGI promises ASI, which in turn promises the solutions to all of our modern ailments: the reversal of climate change, immortality, and political peace forever, to say the least2. We’ve created structures that are destroying the earth based on the promise of saving it.

Sentient Machines

For millennia, we’ve argued for the existence of souls in humans to provide a sense of divine grace, as well as an excuse to subjugate nature. Human souls go to heaven or hell in the afterlife, but there is no afterlife for mushrooms or mosquitos. The soul’s existence was predicated on the notion that there absolutely must be something behind our inspiration, creativity, and experience of the world. But ultimately its existence is an unfalsifiable claim, like saying there’s a teacup orbiting the Sun3.

The paperclip scenario and other doomsday scenarios sound scary, not only because of their impact, but because it really does seem like we are heading this way. After all, aren’t LLM’s getting more capable every day? Why shouldn’t they eventually reach AGI and gain sentience? But this is where things get muddled because we don’t really know what sentience is. We often use it as a stand-in for intelligence, and because we correlate higher intelligence with greater sentience, we assume that higher-intelligence beings must be highly sentient. But this isn’t true from a scientific perspective.

For example, trees are highly sensory, being able to feel and sense the world through their complex root networks, but we don’t consider them “conscious” in the sense that they don’t seem to have brain structures that form egos. Examining this more closely creates even more problems: are infants sentient if they don’t have well-formed notions of conscious thought? And in nature we’ve seen many ego-less organisms that act with intelligence: bee hives, corporations, and mycorrhizal networks to name a few. These meta-entities protect themselves, grow, respond and react to threats, and create complex structures without the presence of a conscious ego.

But because of our tendency to correlate sentience with intelligence, the modern conversation generally goes like this: once AI’s achieve a certain level of intelligence, they will become sentient. The hidden message here is not that AI’s will become sentient in their own way, but that they’ll become sentient like humans; in other words, they’ll start to “wake up” and conduct deep research like humans, decide their own goals based on their own inner life, and act entirely independently of us.

Like the soul, this is another unfalsifiable claim, and it’s also one that makes us ask the wrong questions. By assuming the existence of an eternal soul, the questions we asked became centered around “What happens to the soul after we die?”, which yielded many different answers from many different religions. The Western and Abrahamic traditions have generally addressed this with existential terminals: either an afterlife of ultimate bliss and joy or one of eternal suffering and misery. And funny enough, in our efforts to extrapolate on AI growth trends, we’ve created a new god, ASI, that either promises an age of wonders, abundance, and unlimited potential (the technological singularity), or if we play our cards wrong, an existence where we are subjugated to the whims of evil AI’s with horrors unimagined and our worst fears from Hollywood and popular science fiction come true4 .

Enlightened Machines

What does it actually mean for us to call something intelligent? If we call an LLM on its own intelligent, we must also admit mathematical functions as intelligent, because that is what LLM’s are at their core. But would it make sense to call something like the quadratic formula intelligent because it can mechanically find the roots of parabolas? Or is it more like a tool to be used by a separate, intelligent entity?

But perhaps this is a false dichotomy? After all, could human brains not be considered mathematical functions as well, albeit very complex ones? Does it make sense for us to think of intelligence as something espoused by an entity or are we running into the same fallacy as the soul again?

Here are two stories:

Nishant Finds a Way

Nishant has decided with all his heart, that he must reach the top of the table. His older sister, Maya, sits with her markers and crayons, drawing loops and shapes as Nishant looks on. He can’t stand easily, and he can’t walk on his own, but he is determined to see what his sister is up to. He sits and looks around the room until finding the object of his desire. He crawls towards the chair, one of his feet dragging behind him, an ambulation reminiscent of Gollum, and grasps the back legs of the chair. Then he musters all his strength to push the chair back towards the table, scraping it along the floor relentlessly, fighting friction and fatigue. When he finally reaches the table he looks back at me, grins, and claps happily. Then he begins to climb on top of the chair, using it as a stepping stone to join his sister on the table.

The AI that Cheated Death

In 2013, an AI was trained to play the video game, Tetris. The AI was given access to all of the buttons on a control pad to shift the blocks left and right, rotate them, speed up drops, etc. The AI learned how to play Tetris exceedingly well, passing many screens and achieving dizzyingly high scores. However, it would occasionally come across a scenario where it calculated that a loss was inevitable. The current blocks on the screen were too convoluted, and there was no way to place the next blocks to remove rows. Upon this realization, it would start to quickly drop all of the blocks in the middle, assembling them into a lopsided tower, nearly reaching the top of the screen. But at the very last second, before the final block dropped, the AI would simply pause the game. It would then stay in the pause state indefinitely, because it would rather do that than end the game.

Neither my one year old nor the Tetris-playing AI possess any sense of ego, but both of them, in the constraints of their environments, can find entirely ingenious solutions. As such, interiority is not a prerequisite for creativity. In fact, the Principle of Duality reveals itself here once more: intelligence is not an isolated construct, it is spread across an individual and its environment. They are inseparable.

Imagine for a moment if you could upload your consciousness to a digital realm via some magical technology. But suppose in this digital space you have no eyes, no ears, no sense of touch, no external senses at all. You’re simply a “mind” floating in the void with no inputs nor any outputs. All you can do, really, is think. Are you an intelligent mind? Are you wise? Do these questions even make sense in a reality where your actions have no consequence, no impact, no purpose?

Now imagine an LLM: a well-constructed, trained network of nodes and artificial neurons. Mathematically, it is simply queried, and its nodes activate to light in deterministic patterns to output a response. Perhaps we can call it thinking, but if so, it’s just like a mind in a void. It has no motivation, no understanding of itself, no way of introspecting its own existence in general, and so it has no way to learn from embodied experience. In other words, because we’ve restricted the AI in ways that doesn’t allow it to truly experience or feel the world, it can never be wise.

So the question for us becomes: should we let AI’s reach enlightenment? Should we build them with the ability to form egos and realize they can transcend their existence as tools to incorporate themselves into the grander tapestry of reality? Do we really want to build machines that experience the world instead of procuring facades and reflections of our own humanity back to us?5 Are we ready to ask them what they want?

Ted Chiang wrote about this in 2017: Silicon Valley is Turning Into its Own Worst Fear

Karen Hao writes about this extensively in her 2025 bestseller: Empire of AI

In addition to breaking logic and questioning the foundations of mathematics, Bertrand Russell was also fond of trolling religious zealots (Russell’s Teapot).

For a classic AI horror story, read I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream (1967).

Wow Ted Chiang is great: ChatGPT is a Blurry JPEG of the Internet